|

The grassland across Eastern Europe and Central Asia, the

Steppe, is one of the great highways of world history. Equipped with horses and cattle, people could live easily on the Steppe and move freely across it, all the way from Mongolia to Hungary. From the Second Millennium BC until well into the Middle Ages, movements back and forth across the Steppe, and especially off of it at the periphery, profoundly influenced the history of the surrounding lands in Europe and Asia, particularly Eastern Europe, the Middle East, India, and China. The most dramatic example of this in Ancient times was the descent of the Iranians into the Middle East and India.

Introducing horses and chariots for the first time into these areas of earlier civilization, the Iranian invaders not only revolutionized warfare, but were the ones to reap the first advantages from the innovation. The occupation of the Iranian plateau established their permanent presence there, with the great successor kingdoms of the Medes and the Persians. An Iranian elite, at least, imposed themselves on the Hurrians and the Kassites of the Middle East. With the

Hurrians, the kingdom of the Mitanni then became one of the great second millennium powers of Eastern Syria, while with the

Kassites, an ascendancy was established over

Babylonia. In a 13th century treaty with the Hittites, the Mitanni listed their gods, which are evidently the same gods as in contemporary Iran and in Vedic India.

Recent scholarship has begun to discount to role of the Iranian invaders in the introduction of the horse and in dominating the Hurrians and

Kassites, since horses appear before their arrival and the evidence of the Iranian element among the Hurrians and Kassites is thin. However, the Iranian movement was certainly more that of a migration than the invasion of organized armies. As such, its influences were somewhat more in the way of diffusion than of conquest. Horses arrive before an Iranian population does because they were traded ahead of the migrants.

Someone brought them -- horses (and chariots) did not simply suddenly wander across the Central Asian deserts into the Middle East and India. There is no doubt that horses did

not exist in the 3rd millennium BC in Egypt or

Sumeria. When horses do arrive, they are adopted as quickly as possible. Horses clearly arrived in Egypt with an invasion, that of the Hyksos, but there is no evidence that the Hyksos were Iranians. Whether or not the Hurrians were ever dominated by Iranians, there is undoubted Iranian influence there, with the names of the gods. The gods can have diffused along with the horses. That the Iranians are near is incontestable -- they are soon revealed on the Iranian plateau, and in India, and their languages have been in those places ever since.

Consquently, it doesn't make much sense to completely discount the traditional notions of the role and influence of the Iranians.

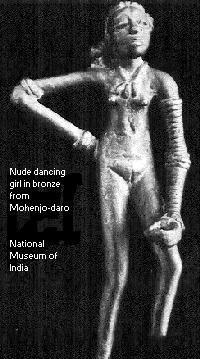

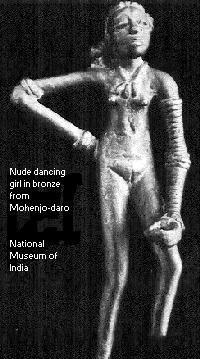

India is where the eastern branch of Iranian invaders, the

Arya, imposed themselves and, erasing whatever establishment or vestiges were in place of the older

Indus Valley Civilization, laid the foundation of a new civilization with their own language and gods. A subsequent Iranian people, the

Sakas, later also invaded India. The Sakas had been dislodged, as the most distant Indo-European occupants of the Steppe, known as the Yüeh Chih (Pinyin

Yuezhi, the "Moon Tribe") to the Chinese, were thrown back into the Tarim Basin (the Lesser Yüeh

Chih) and Transoxania (the Greater Yüeh Chih). The Greater Yüeh Chih, organized as the kingdom of the

Kushans, later continued the tradition by invading India themselves.

Argument continues over the role of the Arya invaders in the end of the Indus Valley Civilization (one of whose famous artifacts is shown at left), which is now usually said to have been in decline and to have come to an end through its own decadence (cf.

The Oxford Companion to Archaeology [Oxford University Press, 1996], "Indus Civilization," pp. 348-351) or natural disasters (cf. "Indus Civilization, Clues to an Ancient Puzzle,"

National Geographic Magazine, Vol.197, No.6, June 2000, pp.108-129). Civilizations, indeed, have their ups and downs. Egypt during its Intermediate Periods, or China after the fall of the

Han, are good examples. However, they rarely

disappear as the result of such low points. Even Mayan Civilization, which essentially did collapse, still left the Mayan people, speaking their own language, behind. It is thus hard to imagine

no connection between the invasion and the disappearance, even as the probable language of the Indus Valley, a Dravidian language, was erased from most of the north of India. Egypt had a tough enough time shaking off the

Hyksos.

Claims are also now made, perhaps not coincidentally starting with Indian scholars, that the Arya originated in India, that the Vedic language is closely related to the Dravidian languages and the source of all other Indo-European languages, and that the hitherto undeciphered Indus Valley script is actually the basis of both the much later (700 or 800 years) Brahmi alphabet in India and even the

Phoenican/Canaanite alphabet of the Middle East. These are inherently suspect and improbable claims, examined in some detail elsewhere.

Since the early Iranian peoples were illiterate, much of their movement and activities remain concealed from history. With the spread of literate civilization, however, much more can the discerned when the entire process of spreading across the Steppe was repeated all over again in the Middle Ages by the Turks.

Moving from east to west, the Turks came as far west on the Steppe itself. But no Turkish presence remains on the European Steppe. The Ukraine remains Slavic, and earlier Turkic peoples like the

Khazars, Patzinaks, and Cumans have disappeared. The Bulgars, originally Turkic, were absorbed by their Slavic subjects. Nor did the Turks settle nearly as much of the Middle East. However, the whole area around the Aral Sea became permanently Turkish, now dignified as "Turkestan," while the defeat of the Romanian/Byzantine Emperor Romanus IV at the battle of Manzikert by the Seljuk Turk Great Sultân Alp Arslan in 1071 opened up Asia Minor, which Iranians had never penetrated, to permanent Turkish occupation and settlement. The presence of

Turkey amidst and upon older Indo-European peoples, the Greeks and the

Armenians, and overlapping an Iranian people, the Kurds, has not made for forgiveness or forgetfulness of their recent advent. Although a Turkish ethnic presence was never established in India, Turkish princes in Afghanistan profoundly influenced Indian history, first by the invasion of

Mahmûd of Ghazna in 1008, when Islâm was first solidly planted in Indian civilization, and by the later invasion of Babur, the first of the Moghuls, in 1526.

The most spectacular and rapid movement of conquest across the Steppe, through the Middle East, and into Europe and China, was that of the

Mongols in the 13th Century. Although several significant and a few durable kingdoms resulted from this conquest

[see the map of 1280 Ad for subsequent developments], little remains by way of permanent Mongol ethnic presence. Only small groups like the Crimean Tartars come to mind. The Mongols thus repeated the earlier, and less well documented, career of the Huns, who also left few durable marks of their presence (like the name "Hungary").

Subsequently, the conquest of the Steppe came from off of the Steppe, especially as the

Russians, who had moved across Asia

north of the Steppe, in the forest land of the

taiga, occupied much of the central

portion of it from the north in the 19th Century. The advent of gunpowder removed the advantage that the horse had given nomadic Steppe dwellers for so

long.

Grasslands at the corresponding latitudes elsewhere in the world did not have the same impact on world history. The

Pampas of South American and the Veldt of South Africa were far too small to provide a highway between different cultural regions.

The Prairie of North America, although extensive, was still not as extensive as the Steppe and lacked the key ingredient: A domesticated animal for riding. Although the horse had actually evolved in North America, it died out there and historically is only found in Asia and Africa (Zebras).

The reintroduction of the horse into the New World by the Spanish set off the development of a romantic Plains culture among American Indian tribes who adopted the horse; but this did not involve the historic transmission of cultures around the periphery, nor did it last very long -- only a century and a half, at most. What these grasslands could mean in modern life was as appropriate ranges to grow a domesticated grass, wheat, and similar agricultural staples. The steppe and similar provinces thus have gone from being highways of history to being

breadbaskets of the world.

Kelley L. Ross,

Ph.D.

TransAnatolie Tour

|